Welcome to the Spring 2018 Newsletter from the Kent

WELCOME

Archaeological Field School

IT’S APRIL AND FOOLS

ABOUND!

UK’S IRON AGE BLING

WHO REALLY FOUND TROY

Dear Member, we will be sending a Newsletter

OPLONTIS EXCAVATION

OPPORTUNITIES

email each quarter to keep you up to date with

news and views on what is planned at the Kent

ARCHAEOLOGICAL WORK

Archaeological Field School and what is

POMPEII. AN

happening on the larger stage of archaeology

ARCHAEOLOGICAL GUIDE

both in this country and abroad. For more

AERIAL SURVEY OF KENT

COURSES FOR 2018

I do hope you enjoy this newsletter which looks

KAFS BOOKING FORM

forward to a summer of exciting

‘digging’

KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM

opportunities. Paul Wilkinson.

Breaking News: It’s April and fools abound!

Patrick Sawyer writing in the Telegraph and footnote by Chris Catling writing in

Current Archaeology:

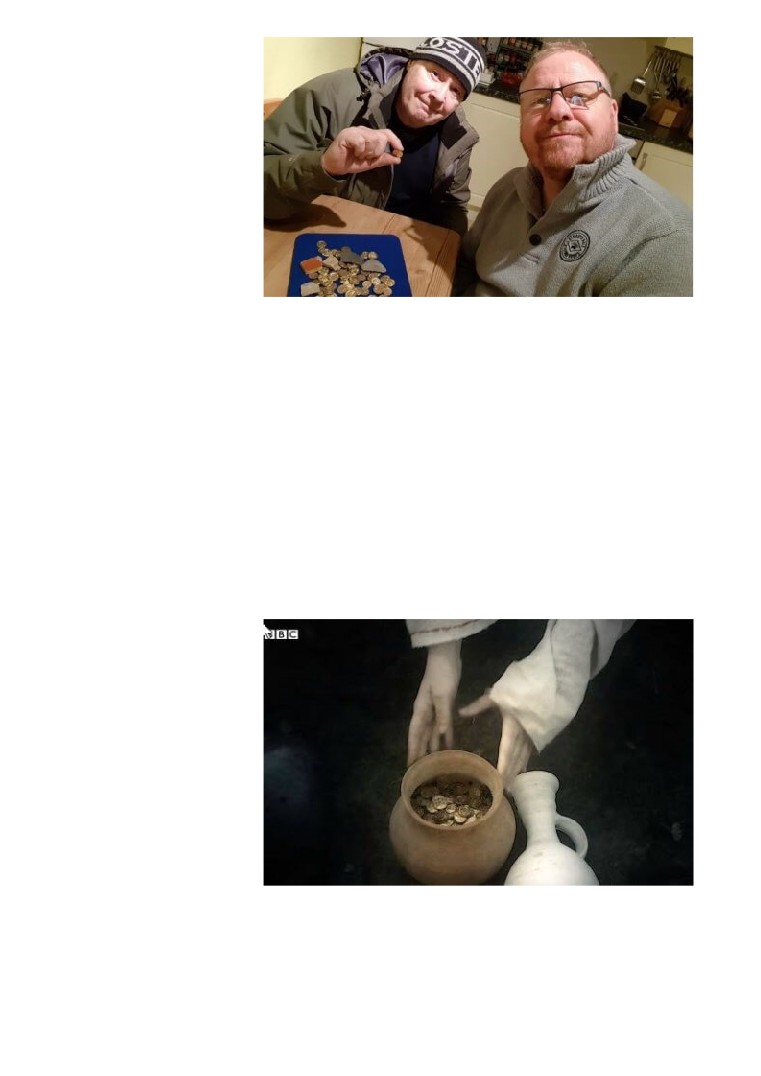

When metal detectorist Paul Adams stumbled on a hoard of gold coins he believed

his luck was finally in.

In all the weeks he had spent carefully scanning fields with his metal detector he

had never before found such a treasure.

With a little jig of delight and a cry of “Roman gold! Roman gold!” Mr Adams called

over his detecting partner Andy Sampson to feast his eyes on the trove, worth what

they estimated might be as much as £250,000.

Pretty soon they started planning how to spend the proceeds of their discovery.

But in what turned out to be a case of life imitating art imitating life, the 54 gold coins

were nothing more than props left behind by a film crew making the BBC comedy

series Detectorists starring Mackenzie Crook and Toby Jones as two hapless friends

dedicated to the search for buried treasure.

During filming of a scene from the first episode of the last series, the replica coins

were shown first being buried in a clay Roman pot (left) before being brought to the

surface by a tractor ploughing a field 2,000 years later.

Unfortunately for Mr Adams, 58, and Mr Samson, 54, when it came to clearing the

set the production company left behind some of the coins, raising the pair’s hopes

when they came across them a few weeks later.

"I think we are officially the world's unluckiest metal detectorists. Our story would

make a TV series of its own,” said Mr Sampson.

"After we found them I was paying off my mortgage and buying a sports car in my

head. We thought we were looking at the real McCoy. Now I look at them and want

to cry."

The pair, who work together delivering oxygen to medical patients, began

detectoring a year ago and had been given permission to sweep the field in Suffolk

where Andy had previously found a Roman coin. As they began searching an area

they could see had recently been ploughed Mr Adams’ machine started pinging.

"I heard Paul shout out 'yes!'” said Mr Sampson, from Ipswich. "I looked up to see

him dancing around. He came floating towards me screaming 'Roman gold, Roman

gold'.

"I ran over to him and was amazed when he showed me a small Roman gold coin in

the palm of his hand.

"We carried on looking and our metal detectors were working overtime, picking out

gold coin after gold coin along a 30ft long furrow.

"We couldn't believe our luck. There were shards of Roman pottery too, which made

sense because the Romans buried them in pots. Everything was as it should be.

"We sat there in total disbelief. I had my head in my hands at one point just because

of the sheer enormity of it all and the feeling of having found a gold hoard.

"We weren't sure how much they might be worth but we had six Emperor Nero coins

and we knew they were worth £26,500 each."

The pair, by their own admission “too excited to think straight”, went home and

planned to inform the landowner and relevant authorities the next day.

But before doing so they showed their find to a neighbour who has been a

detectorist for 40 years and is a member of the Suffolk Archaeological Survey Mr

Sampson said: "He couldn't believe his eyes when I poured them out on the table.

But as soon as he picked one up he said 'these are wrong, they're not real'."

The neighbour informed the pair the coins were in all likelihood fake, but Mr

Sampson refused to believe him, arguing there was no reason for 50 fake coins to

be placed a recently ploughed field.

However, when he told his wife Sam, who works in the estate office of the farm

where they were found, she recalled that the Detectorists had recently been filmed

there.

A call to the production company quickly established that they had put replica gold

coins in the ground for a scene.

Instead of a hoard worth tens of thousands the replicas turned out to be worth a

mere £5 each.

"When my wife told me about the Detectorists filming there an alarm bell went off in

my head,” said Mr Sampson. “She spoke to the location manager and he confirmed

they were props. We didn't know whether to laugh or cry. "

Mackenzie Crook, 46, who wrote, directed and starred in Detectorists, said he was

'horrified' to learn that the pair thought they had uncovered a Roman hoard.

The Bafta winner said the crew picked up as many replica coins as they could after

filming. He said he intended to go back to look for more but was beaten to it by the

duo.

Mr Crook said: "Unfortunately, that day we didn't have metal detectors with us and I

intended to go back to find any strays.

"But freshly ploughed fields are magnets to detectorists and the next day I was

horrified to hear that Paul and Andy had got there first and found what they thought

was a hoard.

"As a detectorist myself, I'd like to assure these gentlemen that I was gutted that I

might have contributed to their disappointment. I hope they continue searching and I

hope they find their real gold soon."

However, Christopher Catling writing in Current Archaeology says: ‘could Paul and

Andy living locally, not be aware that a film crew with all its paraphernalia spent

several weeks filming the TV series in that field, especially as (real life) Andy’s wife,

Sam, works in the estate office of the farm that owns the field- it was she who

‘recalled that Detectorists had recently been filmed there’ and spoke to the location

manager who confirmed the coins were props’. Not exactly fake news, but perhaps

a story concocted with much of an eye for entertainment as for strict veracity’.

Footnote by Christopher Catling writing in the recent edition of

Current Archaeology (Issue 338):

Professional Archaeology:

The Enemy

Until recently, the script [of the Detectorists] steered clear of the mutual suspicion

that exists between archaeologists and detectorists, but that serene balance was

upset by the third and last series, which has just been broadcast (so spoiler alert

ahead!). The gentle humour took a somewhat unexpected turn when nice, wise, and

thoughtful Andy - played by Mackenzie Crook, who also wrote the series - gave up

his job mowing verges for the Council to become a contracting archaeologist. His

first day on site, he uncovered the edge of a Romano-British mosaic and he

dreamed about it all night. The next day, when he turns up on site with JCBs

manoeuvring menacingly in the background, the mosaic cannot be found.

Was it just a dream? Where has it gone?

Andy turns to his site supervisor, portrayed as lazy, shifty, and devious: a soulless

man with a blank stare and machinelike speech, a man who prefers the warmth of

the site hut to real archaeology. He tells Andy with a shrug of the shoulders that 'it

had to go' because the archaeologists have to be off site at the end of the week.

Andy resigns his job on the spot, and, in that one short scene, professional

archaeologists are thus dismissed as mendacious and hypocritical individuals, in

league with those same developers who are destroying Andy's beloved countryside.

Sherds now finds his enthusiasm for the series dented, and it is difficult to

recommend it unreservedly; it needs a health warning. Distressingly there has been

no outcry from archaeologists. Imagine how outraged the detectorist community

would be if they were all portrayed as get rich- quick cowboys, only interested in the

monetary value of their finds, pillaging our common inheritance for personal gain.

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/2:

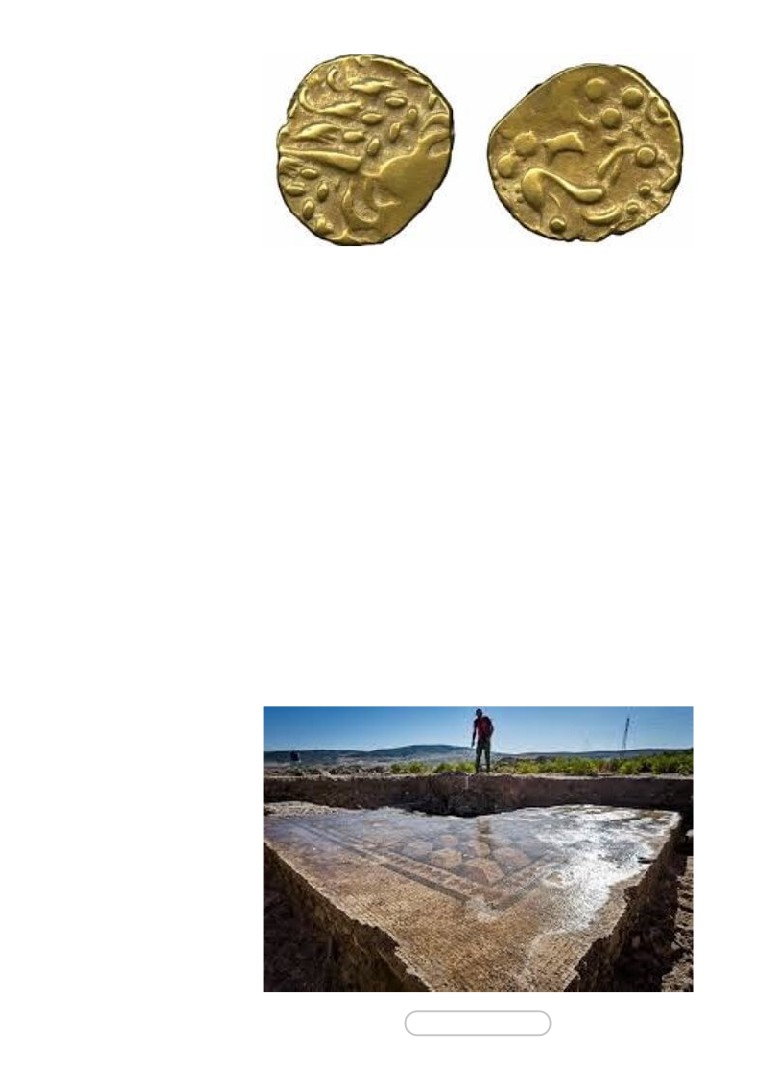

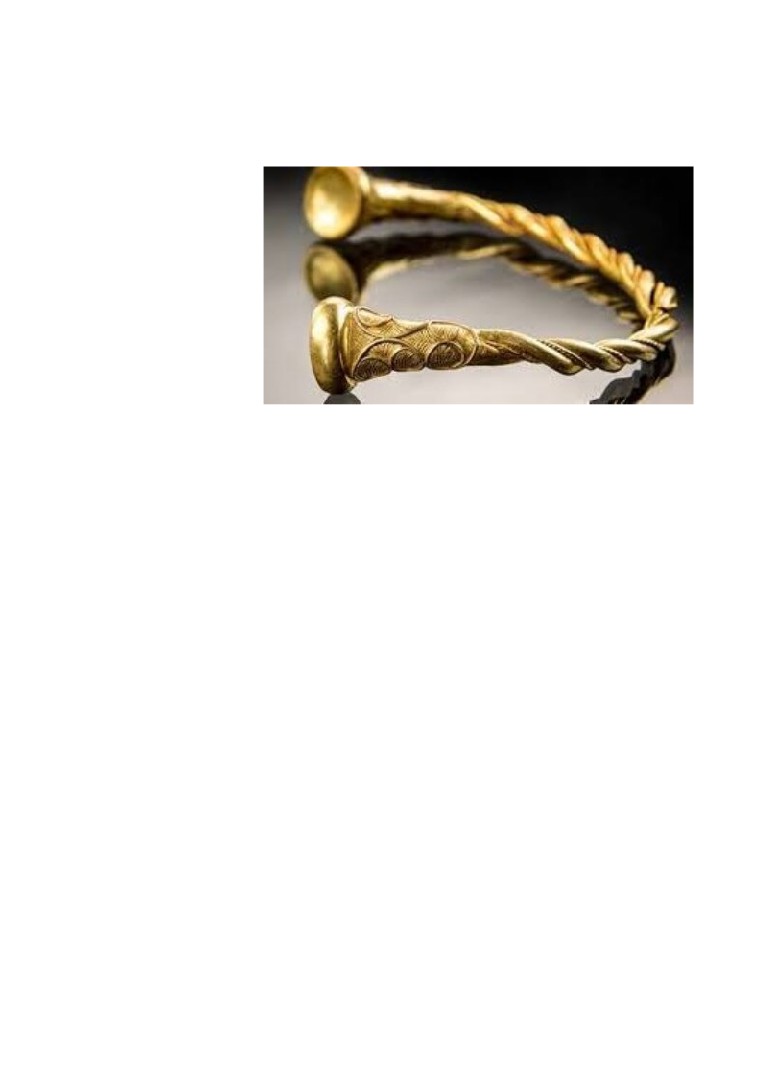

UK’s Iron Age bling reported by Norman Hammond

writing in the London Times

It would have made Andy proud. The Iron Age gold jewellery found a year ago by

the real-life counterparts of BBC Four's Detectorists has been hailed as one of the

ten most important discoveries of 2017 by a leading American journal.

Noting that the three torcs — two necklaces and an armlet — and the two-strand

twisted bracelet dating from 400-250BC are so "remarkable", the Archaeological

Institute of America's Archaeology puts them alongside traces of Neanderthal DNA

in caves across Europe and the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs as the notable finds of

the year.

For several hundred years previously, Britons "appear to have largely abandoned

wearing and manufacturing gold jewellery", the journal notes.

When iron supplanted bronze as the main metal for tools and weapons, the trade

networks that funnelled copper and tin across Europe broke down, and "communal

identity might have been more important than things which emphasise an

individual's power, like wearing loads of bling", says Julia Farley of the British

Museum.

The find, uncovered at Leekfrith in Staffordshire, was declared treasure at an

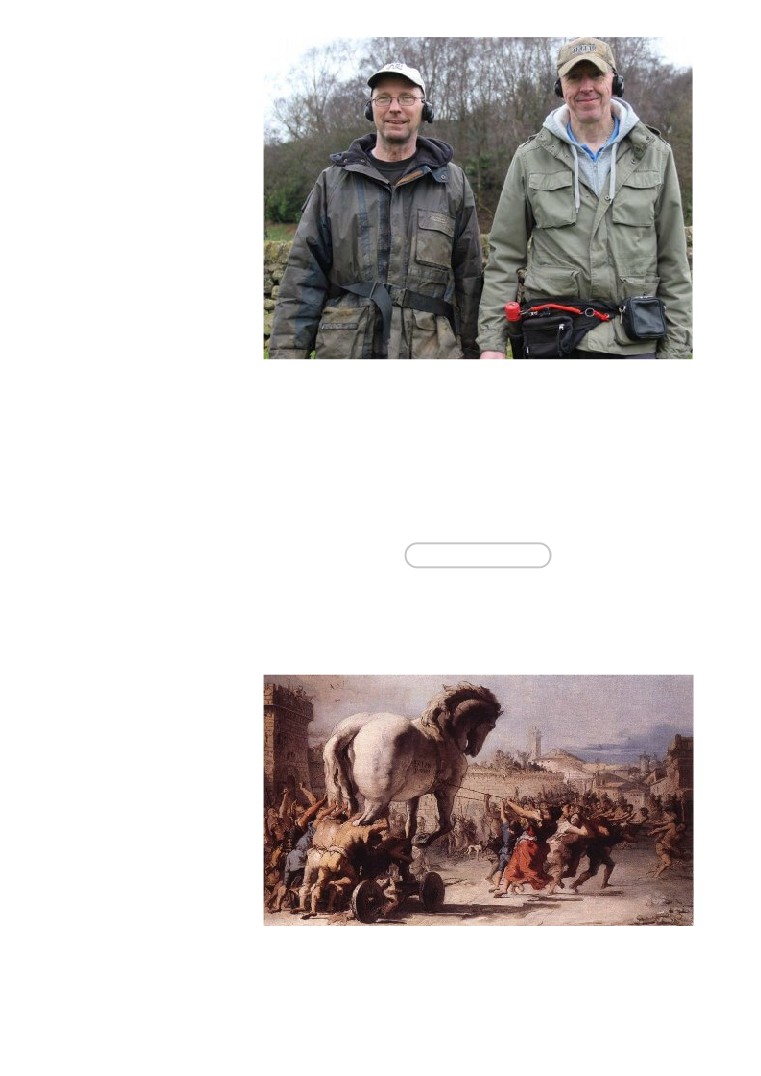

inquest in February, two days after the real detectorists. Joe Kania (left) and Mark

Hambleton (right). had found a missing piece of the smallest tore. The hoard was

valued at £325,000, and the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Hanley launched

an appeal to acquire it.

A second British site made it into Archaeology's 2018 top ten: the discovery that

inside the great megalithic stone circle at Avebury in Wiltshire there had once been

a square formation of stones. Mark Gillings of the

University of Leicester believes it to have commemorated the footprint of a Neolithic

house from as early as 3500BC, a millennium older than the stone circle, and that

the latter was built to enclose what was "an ancestral place that had slipped into

myth and legend".

At the recent end of the archaeological timescale, Archaeology includes in its

remarkable finds of 2018 the skeleton of a 15th-century Aztec wolf, sacrificed and

buried with gold adornments at the foot of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan in

Mexico City.

There is also a 1911 Huntley & Palmers fruitcake, left in Antarctica's oldest building,

on Cape Adare, by Captain Scott's expedition on its way to the South Pole, and still

"in fine shape", but with "that slightly off smell of butter that's gone wrong", according

to Lizzie Meek of the Antarctic Heritage Trust.

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/3: Who really found Troy?

Ben Macintyre of the London Times explains

Love, war, revenge, fire, gods, trickery, swords and sandals: the siege of Troy, the

greatest story ever told, and retold, is returning in a new eight-part television series

in the spring.

A British-made version of the great legend is an opportunity to correct a long-

running myth and give Britain credit where it is due: contrary to popular belief, the

remains of Troy were discovered not by the unscrupulous German adventurer who

has claimed credit for the past 140 years but a self effacing English gentleman-

scholar and a Scottish journalist.

Only slightly less dramatic than the story of Troy is the tale of who really found it, a

saga of Anglo- German conflict, multiple layers of skulduggery and a treasure trove

looted by Soviet soldiers at the end of the Second World War, now held in a Moscow

museum. By rights, part of the hoard should be in Britain.

Heinrich Schliemann was a self made, self-taught German magnate who made a

fortune selling ammunition to Russia during the Crimean War. Schliemann claimed

to be the first to correctly identify Hisarlik in western Turkey as the site of Troy,

where he uncovered a great trove of gold, silver and bronze artefacts in 1873.

He kept the public informed of his exciting discoveries with reports in The Times. He

also found a gold funeral mask and supposedly wrote, in a telegram to the King of

Greece: " I have looked upon the face of Agamemnon."

No, he hadn't. Some of Schliemann's claims were wrong and many were

deliberately misleading. The so-called Father of Mediterranean Archaeology was a

prodigious liar.

The first person to identify Hisarlik as the lost city of Troy, back in 1822, was Charles

MacLaren, a Scottish farmer's son who founded The Scotsman. Working from

literary clues left by Homer, MacLaren correctly pinpointed Hisarlik, a mound on a

strategic hilltop close to the Dardanelles, as the "city of heroes" described in The

Iliad.

That revelation was taken up by Frank Calvert, a shy, unmarried English consular

official and amateur archaeologist. He purchased a farm incorporating half of

Hisarlik Hill and in 1863 he started digging. The British Museum declined to help, so

he dug on alone.

Schliemann turned up seven years later, on an extended tour with a new Greek wife

30 years his junior. Calvert showed him around the site and effectively introduced

him to archaeology — about which he was, until that point, largely ignorant.

Schliemann noted "the rich collection of vases and other curious objects that the

ingenious and indefatigable archaeologist Frank Calvert has found". He also sensed

an opportunity for fame. The ambitious German then launched what was, at the

time, the biggest archaeological excavation ever undertaken.

Mobilising an army of 150 workers, whom he dosed with quinine to protect against

malaria and forced to work 13 hours a day, Schliemann tunnelled through layer

upon layer of history in search of Homeric Troy (the site contained at least nine

successive cities, built one on top of another) and by 1871 he had excavated an 18-

metre hole.

Schliemann then announced he had uncovered the treasures of King Priam, a

fabulous hoard of gold, jewellery, weaponry and vases.

In fact he had blasted through the Troy of Homer from the late Bronze Age to find

the artefacts of a civilisation at least 1,000 years older.

When Calvert made this point, the two men fell out dramatically.

Schliemann then smuggled his finds out of Turkey.

Later archaeologists have questioned not only the dating but also the provenance of

Schliemann's discoveries, amid suspicions that he may have "salted" the site with

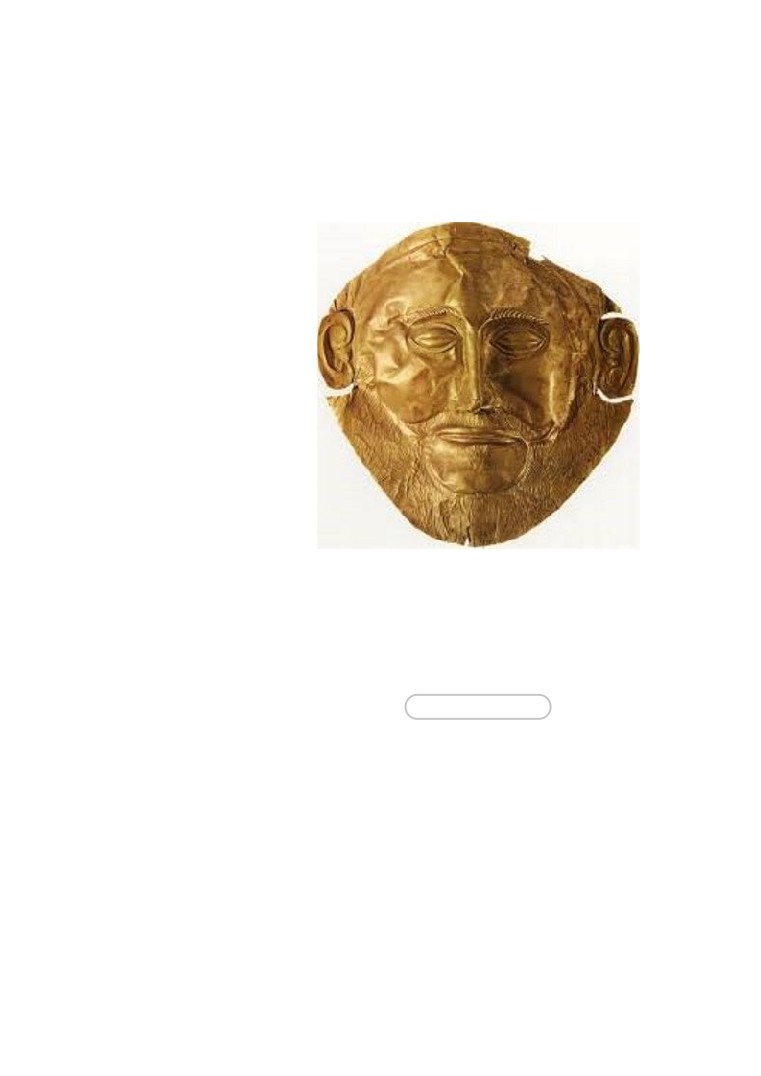

objects found elsewhere. In 1876, at Mycenae, he found the Mask of Agamemnon,

now on display in Athens and described as the "Mona Lisa of prehistory". Modern

research, however, indicates that the mask predates the Trojan War by several

hundred years. It may even be a fake.

Ruthless in his self-promotion, Schliemann claimed all the glory and airbrushed

Calvert and MacLaren out of history, making it seem that he alone had found the

site, equipped only with a copy of The Iliad.

He unscrupulously rewrote his own life, depicting his discovery of Troy as the

crowning achievement of an ambition inspired by reading Homer as a boy, rather

than a chance meeting with a British official during a luxury holiday.

His Athens mausoleum bears the inscription "Schliemann the Hero".

The descendants of the Calvert family claim a portion of the Trojan treasures, since

some artefacts, including a collection of ceremonial axes, were found on their

family's land but not shared with Frank

Calvert. Schliemann presented his collection to the German government with great

fanfare. In the final days of the Second World War it was carted away from Berlin by

Stalin's "Trophy Brigades" as part of the systematic plunder of Germany. The axes

were thought to have been lost until they were put on display at the Pushkin

Museum in 1994 along with other pieces of 'Priam's Treasure".

The trove is claimed by Russia, Germany, Turkey and Greece. Calvert's heirs are

reportedly also planning legal action to get some of the treasure back.

The Mask of Agamemnon (above) which some experts have claimed is a fake

For centuries many believed that Troy was a myth, the product of an inspired poetic

imagination. Calvert proved it was genuine history.

The new BBC series, jointly produced with Netflix, will offer fresh homage to Homer

but it also enables us to recognise the forgotten victor in the hunt for the fabled city.

Calvert died in 1908, an unassuming British Indiana Jones and the real hero of Troy.

BACK TO MENU

Breaking News/4:

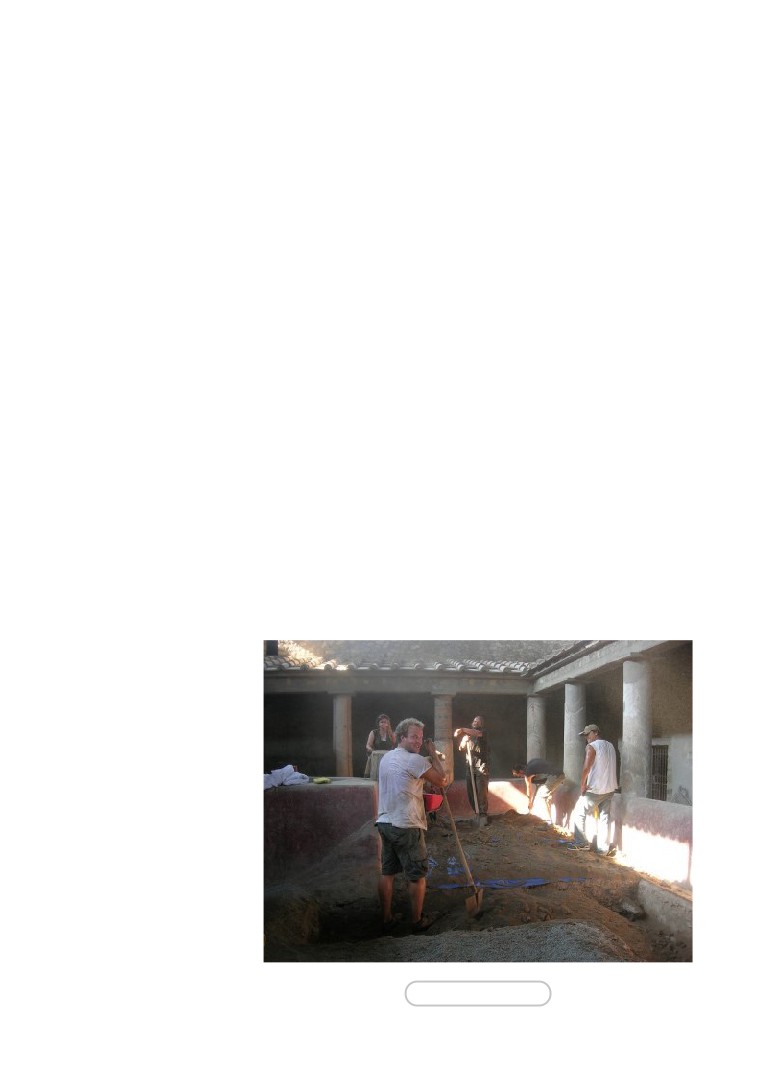

Oplontis excavation opportunities for the 30 lucky

archaeologists who gained places on what could be the last

dig at this iconic World Heritage site

The Oplontis Project began in 2006 with the study of the site known as Oplontis

situated at Torre Annunziata, Italy. The work is sponsored by the Center for the

Study of Ancient Italy at the University of Texas in Austin. Its two directors are John

R. Clarke and Michael L. Thomas. In addition the Kent Archaeological Field School,

Faversham, Kent UK under its director Dr Paul Wilkinson has been involved in

fieldwork at both villa sites since 2008.

The aims of the project are to enable an understanding of the two buildings, one of

which is Villa ‘A’, the other Villa ‘B’ to be enhanced through a comprehensive study

of the buildings, the fabric, the artefacts and human remains, their location, and their

function including a 3-d model (above) with interactive database which will enable

scholars to write a series of comprehensive volumes which will be published by the

Humanities eBook series of the American Council of Learned Societies. The first is

scheduled to appear in 2014.

Villa ‘A’ is now recognised as one of the most sumptuous and extravagant Roman

villas overlooking the Bay of Naples. It is thought by many that the villa was the

property of Poppaea Sabina the Younger who was born in Pompeii in AD30 and

married Nero in AD62. The evidence is somewhat circumstantial and consists of

graffiti found on an amphora which said ‘secundo poppaea’ which in translation

means ‘to the second [slave or freedman] of Poppaea’.

The villa was excavated by an Italian team over twenty years ago, and although it

was impossible because of modern development to find the limits of the villa some

99 rooms and spaces were excavated including a sixty metre swimming pool and

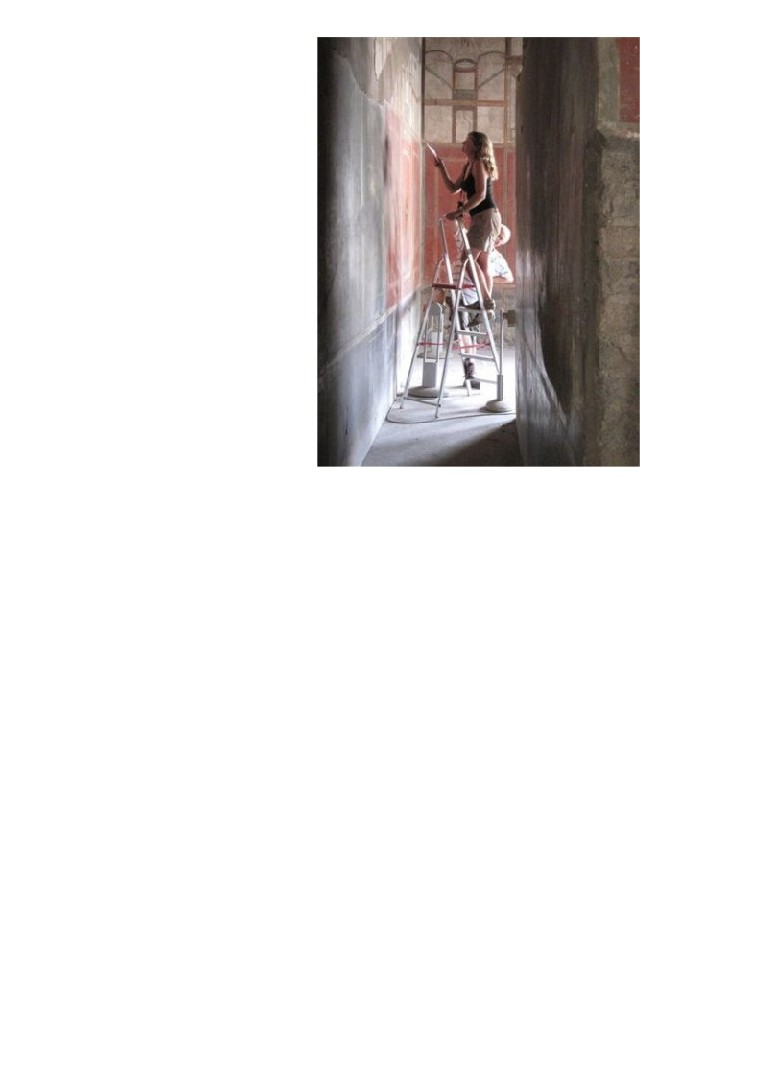

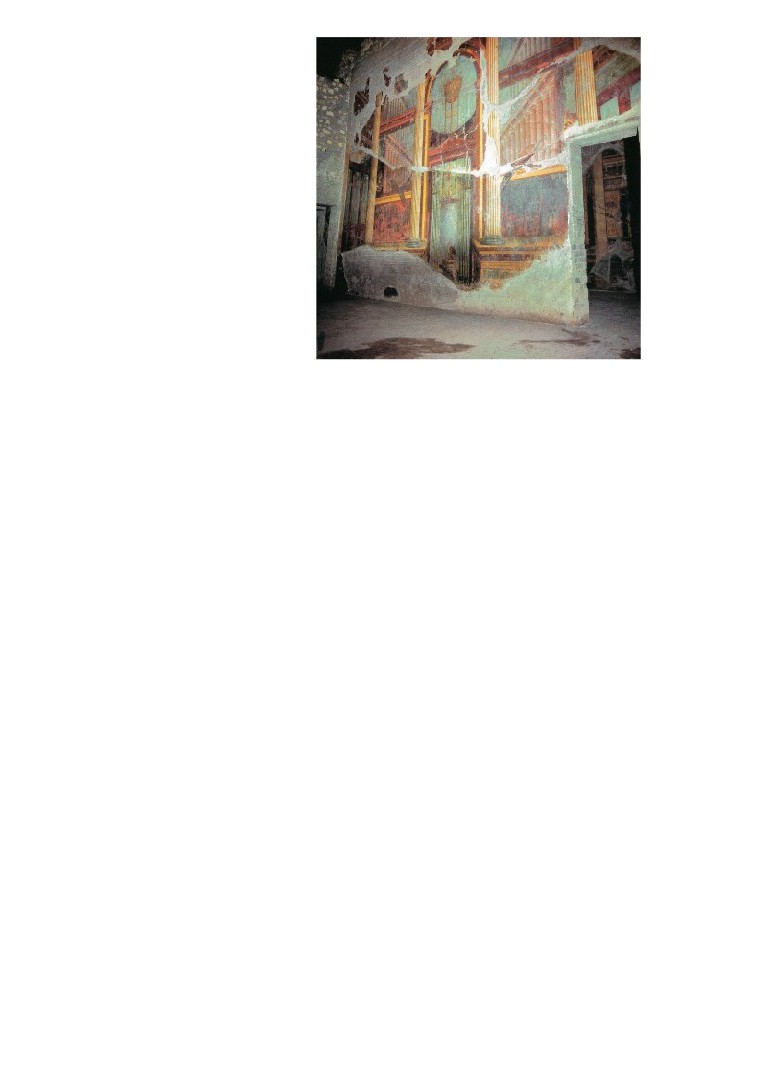

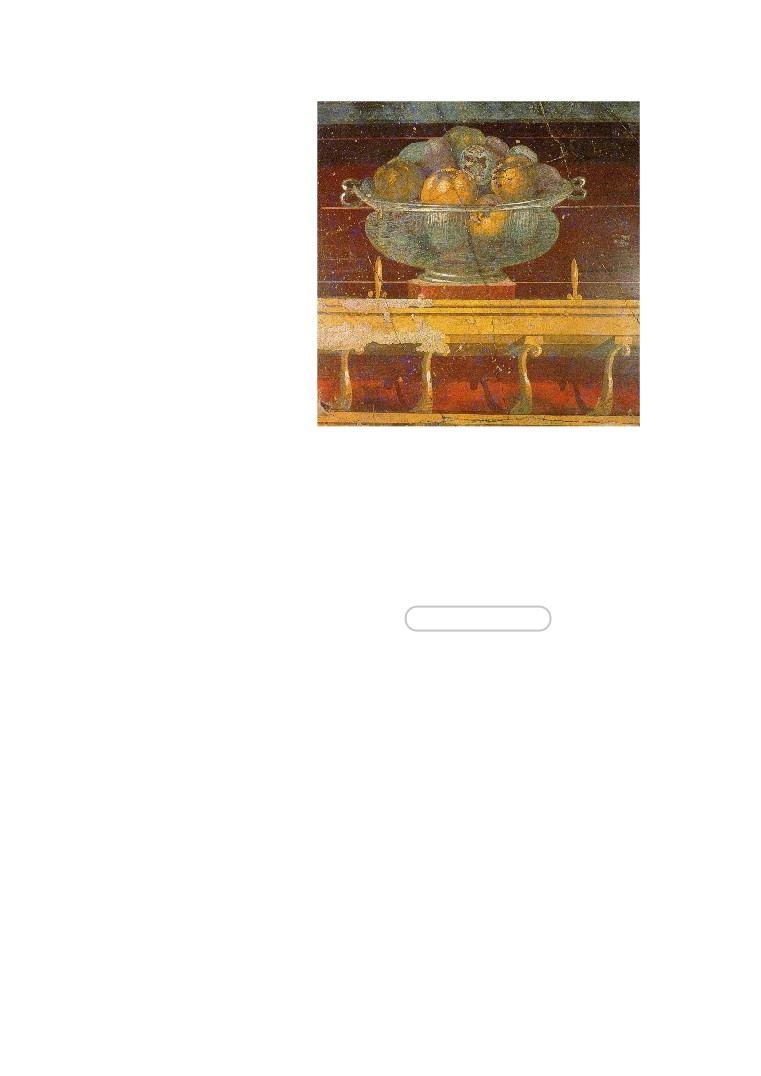

formal gardens. The villa is probably best known for its wonderful Second Style wall

frescoes which can be found in a number of rooms located around the atrium, itself

dating back to about 50BC.

Villa ‘B’ is located about 300 metres to the east of Villa ‘A’ and is not a villa. Its likely

function was a warehouse where wine would be processed and shipped out in

amphorae. Some 400 amphorae still litter the site. Around the warehouse are roads

and streets of town houses still waiting to be excavated.

The plan of the warehouse is focused on a central courtyard surrounded by a two-

storey peristyle of Nocera tufa columns. The eastern side of the peristyle includes

an entrance opening onto an unexcavated road running north south and detected

through our coring campaign. Ground floor storage rooms open up into this central

space whilst above on the second floor are residential rooms. To the south lies the

remains of a colonnade and portico and, set back, a series of large barrel vaulted

storage rooms which faced the sea. In these rooms, just as in the Roman port area

of Herculaneum, dozens of skeletons were found of people waiting to be rescued by

boat from the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79.

In 2008 I was invited by John Clarke to join the team and started work on site at Villa

‘A’ helping with a small evaluation trench located in the southern area of the large

swimming pool. One of its aims was to attempt to date the adjacent foundation wall

of Room 78, the large diaeta (private room) to the south-west of the swimming pool.

We excavated through demolition layers of Roman material which included

fragments of exquisite fresco, painted stucco fragments and, the most wonderful of

all, beautiful oil lamps with a variety of designs. To an archaeologist who normally

excavates Roman sites in Britain the quality and quantity of finds was staggering.

The Fourth Style fresco fragments indicated a terminus post quem date of about

45AD for the construction of the diaeta (above).

The following year I returned to Oplontis with a small team from the Kent

Archaeological Field School (KAFS) and a Landover full of archaeological kit. The

drive from Kent, through France, across the Alps and down the spine of Italy was

memorable and is something I still look forward to every year. In a way it is a drive

through a historic lanscape, and gives one a feel of how extremes and opportunities

of landscape moulded the lives of past peoples. The 2009 season was busy and

eight trenches were excavated at Villa ‘A’. In addition Giovanni Di Maio who had

already undertaken some work on the geological formations below the villa cored

three additional areas to the south of the villa and proved that Villa ‘A’ was situated

on a cliff about 13 metres above the Roman sea level. Our work in 2009 included a

test pit dug through the north-west corner of the pool. We found that the pool had

originally been larger and had been reduced in width presumably to allow the

colonnade of porticos on the west side to be built. In addition we excavated part of a

circular fountain in Room 20. It had been revealed by workmen laying cables in

2007 and not recorded. On investigation we found a partly demolished fountain

buried under a metre of demolition debris. The fountain had quite a pronounced tilt

to it which might suggest Villa ‘A’ had been subjected to serious earthquake damage

in the years before AD79. All the piping to the fountain had been robbed, and in

addition a statue which graced the south edge of the fountain was no longer there,

but its concrete ‘footprint’ was!

Another of our trenches was located in the north-east corner of the north gardens

and for once we were digging through layers of pumice deposited by the volcanic

eruption of AD79. Underneath we found an open canal 80cm in width and finished in

coating of cocciopesto (pink waterproof cement), known to archaeologists as opus

signinum. The canal runs north with a slight curve to the east under the modern car

park. The function of the aqueduct fed canal cannot be proved, but it is likely that it

was an open water feature, part of an elaborate garden which went out of use in

antiquity when it was backfilled with earth and debris.

Another garden we looked at was in Room 32, the peristyle in the servants quarters

located to the east of the main atrium. We discovered evidence for an earlier

peristyle that matched the footprint of the later build. The trench produced copious

amounts of marble mosaic flooring, opus signinum slabs, and the exquisite marble

nose from a small statue! The water features investigated in 2009 suggest that the

first phase of the villa dated to about 50BC, and was seriously damaged in the

earthquakes of AD62 with the water features decommissioned and either

demolished or backfilled. In

2010 we excavated nine trenches with a view to

unravelling the complexities of the water supply to the villa. In the south-east of the

north gardens we excavated a large cistern with a capacity of about two cubic

metres of water. It seems the cistern, constructed of opus signinum, was to prevent

flooding in this part of the garden, to hold a water supply for the garden, and for use

as a drain to the nearby portico that once lined the eastern side of the north garden

and its adjacent room. The finds from the infill of the cistern were dazzling with large

fragments of a Doric frieze constructed of super fine stucco, two types of antefixes,

and part of a column constructed of wedge-shaped bricks and with stucco flutes. It

was decided to excavate in the centre of the 60m swimming pool which required

crowbars to remove the large basalt blocks which made up the substructure of the

pool. Our daily water consumption went up from two litres a day in the shade to six

litres! The reason for digging was that the ground penetrating radar had found a

significant anomaly underneath the pool foundations. Unfortunately we did not find

any anomaly but we did expose and record the two phases of pool construction, the

eruption layers and the palaeosoils.

Our attention then focused on the area immediately south of the pool. Four trenches

were dug that exposed a portico at the south end of the pool, part of a wonderful

marble floor of opus sectile, a room not recorded before with marble steps and a

Doric column with stucco fluting still in situ. Found on these steps were copious

amounts of pottery and a large piece of marble architrave with part of an acanthus

scroll or volute (opening picture).

Our work at Villa A has gathered additional evidence that after the earthquake of

AD62 large areas of the villa were badly damaged The finding of part of a column

drum from the adjacent east wing in the cistern, the lifting of part of the opus sectile

floor prior to the eruption of AD79, and the remodelling of the swimming pool

suggest that major re-building work was being undertaken. The villa also had

problems with its water supply which may suggest that the villa was not habitable at

the time of the eruption in AD79.

BACK TO MENU

Archaeological work so far:

Initial GPR work had detected a series of anomalies that suggested the presence of

earlier structures under the present exposed buildings. In particular the investigation

suggested that the complex lay just a few metres from the ancient shoreline. The

wider settlement may have been a small town (Oplontis) or a commercial harbour

serving the Pompeian countryside, and will be the first of its kind discovered in the

Bay of Naples area.

Work started in 2012 in the courtyard area with the aim of exposing the stratigraphy,

and to examine the foundations of the building which may produce evidence of its

function and chronology. We expanded the trench to the entire width of the

courtyard and soon had to resort to crowbars as the original surface of the courtyard

comprised large and occasionally very large basalt boulders with the gaps between

boulders infilled with large sherds of amphorae. Some of these still retained residue

which were bagged for analysis.

Immediately under the basalt pavement was the first of many pyroclastic flows, the

first dating to the Late Bronze Age. As we excavated down we exposed and

recorded sequence after sequence of eruption strata and palaeosoils dating as far

back as 1500-1600BC. Some of these surfaces had carted or sled ruts along with

pottery sherds and remains of mud bricks. The lowest strata were littered with

Bronze Age artefacts, and suggest there was a high level of Bronze Age activity in

the environs of Oplontis B.

Both ends of the trench gave an opportunity to investigate the foundation design of

the colonnade which was unusual to say the least. A thick tufa stylobate sits on top

of foundation blocks (sterobate) spaced to coincide with the joins between the

blocks of the stylobate with the entire assemblage sitting on the same pyroclastic

stratum which we found under the basalt paved courtyard. Sherds of Campania A

Black Gloss pottery found in the foundation trench date the build of this colonnade

to the 2nd century BC.

In 2013 we returned to this area and expanded the trench to expose a complex

water system with a settling tank plus two water channels and various drains. Of

some importance is the fact that this complex water system cut through two

previous floor levels which suggests the function of the building may have changed

through time. Another team undertook the task of removing tons of modern debris in

the area of the south portico. A thankless task undertaken in the glare of the Italian

sun! But well rewarded by exposing layers of volcanic debris from the eruption of

AD79. Underneath this layer we found the original floor surface with numerous

Neronian and Flavian coins. Below that a complex of barrel vaulted drains was

exposed which will need further investigation. Our final investigation was to examine

part of the street north of the main complex. Originally excavated by the Italian team

in the 1980’s, who discovered a street running east to west lined on both sides with

simple town houses on both sides, it is apparent that these houses have ground

floor rooms, some with the foundation step of a staircase leading to upstairs rooms,

and some of which have a simple shrine dedicated to the household gods. Our

investigation showed that some areas of the ground floor still retained debris from

the AD79 eruption and had not been excavated. Underneath we found a simple

beaten earth floor, the step for a staircase, a toilet and washing area and probably a

kitchen area. The road outside the house was also excavated and showed it had

two construction phases which may correspond to the two identified phases of the

adjacent building, the first probably dating to the 2nd century BC when the building

were probably used as workshops with a wide entrance, and the second phase

when the entrance was narrowed and the building turned into domestic quarters.

Indeed, three houses show walled up entrance’s, it now became a typical Roman

street that included stone benches outside of each entrance

We will be back in Oplontis in June 2018 for another season of excavation and

unfortunately there are no places left on our team. For further information see the

website for the project at

Paul Wilkinson of the Kent Archaeological Field School - www.kafs.co.uk

BACK TO MENU

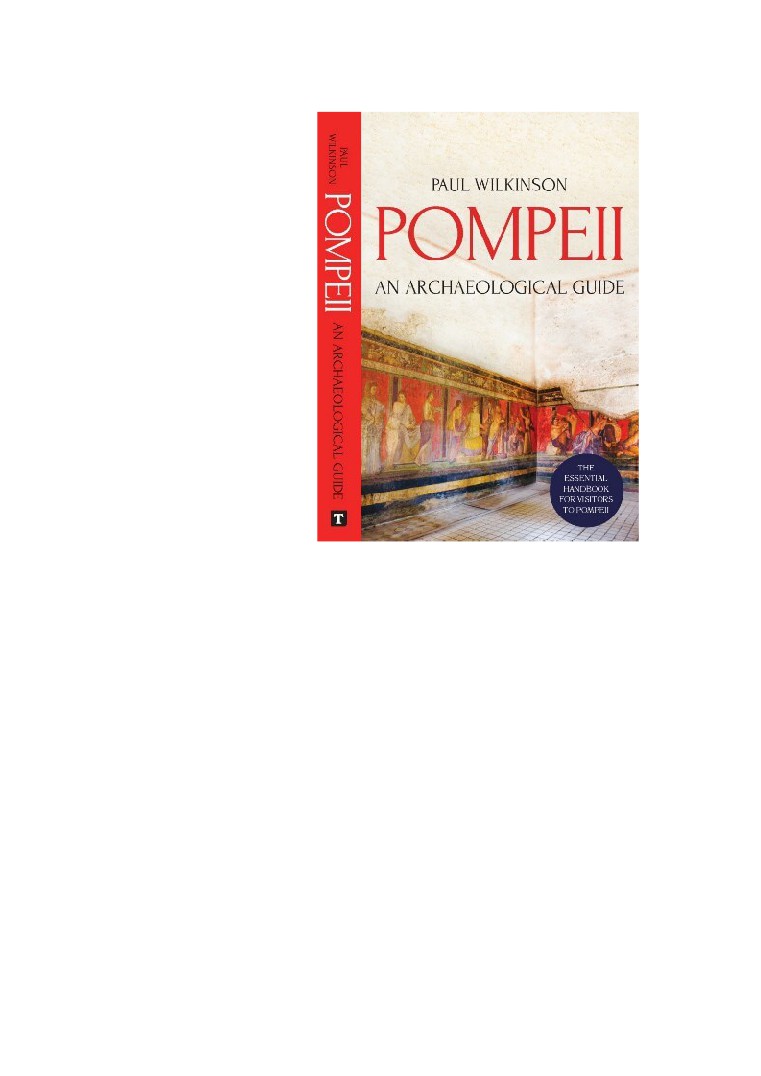

Book of the Month is:

Pompeii. An Archaeological Guide

I B Tauris 2017

£12.99, ISBN 9781784539283

“Pompeian pilgrims will be in good hands with Paul Wilkinson, an old Pompeian

hand, archæologist, journalist, tour-leader and BBC documentary maker”.

‘A Guide to Further Reading’ combines Wilkinson’s favourites (Mary Beard tops the

list

- see her Pompeii [2008, Fires Over Vesuvius in US]) with a five-page

Bibliography, to which I’d add: Kristina Milnor, Graffiti

& the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii (2014) and Ingrid Rowland, From

Pompeii: The Afterlife of a Roman Town (2014). Also, Carlo Avvisati’s Pompeii:

Mestieri e Botteghe 2000 anni fa (2011), compared to Wilkinson’s earlier Pompeii:

The Last Day (2003), generally to the latter’s advantage by David Noy (Bryn Mawr

Classical Review, 2004. 03. 51). Wilkinson laudably cites websites, but could have

Since many visitors will also take in Herculaneum, it’s worth remarking the

excitement at the prospect of opening and deciphering the 700 or so charred

papyrus rolls unearthed in a villa that may

(or may not) contain lost literary

treasures. Statius’s verses (Silvæ 4. 4. 78-86) on hopes for future excavation and

fears of more Vesuvian fires might have been quoted.

Users will thank Wilkinson for his ‘Glossary of Latin terms’, though something has

gone awry with the bilingual ‘Ministry Fortuna Augusta’. The plural of balneum is

wrong, whilst ala is understood to mean ‘bedroom’: it can denote ‘recess’, not

necessarily a boudoir.

One word conspicuously absent is lupanar (brothel), an area no visitor will miss. Of

the 32 colour plates, one shows Priapus urinating from his brobdingnagian phallus,

and another, a jolly scene of Roman rumpy-pumpy. Otherwise, erotic details are

rationed.

Those who want more - and who wouldn’t? - should apply to Michael Grant’s

unmentioned Eros in Pompeii.

The index is serviceable, though somewhat choosy on no obvious principle,

especially regarding the names of modern scholars. After a tersely helpful Timeline

from antiquity to AD 1997, the Introduction and trio of chapters survey everyday life

in Pompeii, plus detailed descriptions of the Amphitheatre Riot of AD 59 and the

eruption itself, with full transcriptions of Pliny the Younger’s pair of autoptic

accounts.

These pages display how well Wilkinson knows his Pompeian onions.

A few minutiæ: Wilkinson’s urban-rural dichotomy regarding dislike of toga wearing

misleads. Augustus rebuked the populace for neglecting it, and Horace describes

Romans at large as ‘tunic-clad’. Lack of private baths and dubiety over marital

bedroom arrangements could have been mitigated by such sources as Petronius

and Seneca.

One hot potato not grasped is whether or not there was a Christian and/ or Jewish

presence. Mary Beard dismisses this (cf. the online essay by Thomas Wayment &

Matthew Grey) as “a fantasy” - odds are the notion derives from Bulwer- Lytton’s

Last Days of Pompeii, which contains a group of such Pompeian brothels and

erotica get short shrift, but barring a few (fairly minor) errors, this is an excellent

guidebook for the curious visitor religionists. Sergius Orata might have been given

full credit for hanging-baths and oyster entrepreneurship, and I’d like to know

Wilkinson’s view of that age-old chestnut: which side of the road did the Romans

drive?

This book stands or falls with the archæological sites-guide that makes up its

second part.

Here, Wilkinson is faultless.

His diagrams are clear, the relevant information dispensed without fuss, with due

acknowledgement to the many archæologists and epigraphers involved. All this

written in clear, jargon-free English, nicely leavened with wit.

The Romans had Pompey the Great. In Wilkinson, we have a Great Pompeian.

Professor Barry Baldwin writing in the Fortean Times

Five Stars awarded

BACK TO MENU

Research News: Aerial survey of Kent. Paul Wilkinson reports on a research

project by the Kent Archaeological Field School

‘If you are studying the development of the landscape in an area, almost any air

photograph is likely to contain a useful piece of information’

(Interpreting the

Landscape from the Air, Mick Aston, 2002).

Students of the KAFS have extended the two year programme of collating Google

Earth aerial photographs from

1940 to 2018 to five years to enable focused

information which can then be followed up by ground survey. The fruitfulness of this

can be appreciated by the work of the field school along Watling Street in North Kent

where hundreds of important archaeological sites have been identified. The ultimate

aim is to publish the results online. Aerial photography is one of the most important

remote sensing tools available to archaeologists.

Other remote sensing devices that will be used are satellite imagery and

geophysics. All of this information can be combined and processed through

computers, and the methodology is known as Geographic Information Systems

(GIS). Readers are invited to send in their aerial photographs to the data base and

WWI practise trenches alongside the A2 between Bridge and Lyden

BACK TO MENU

Courses at the Kent Archaeological Field School for 2018

include:

May Bank Holiday Friday 25th May to Monday 28th May2018: An Introduction

to Archaeological Survey and Test-Pitting at Wye in Kent

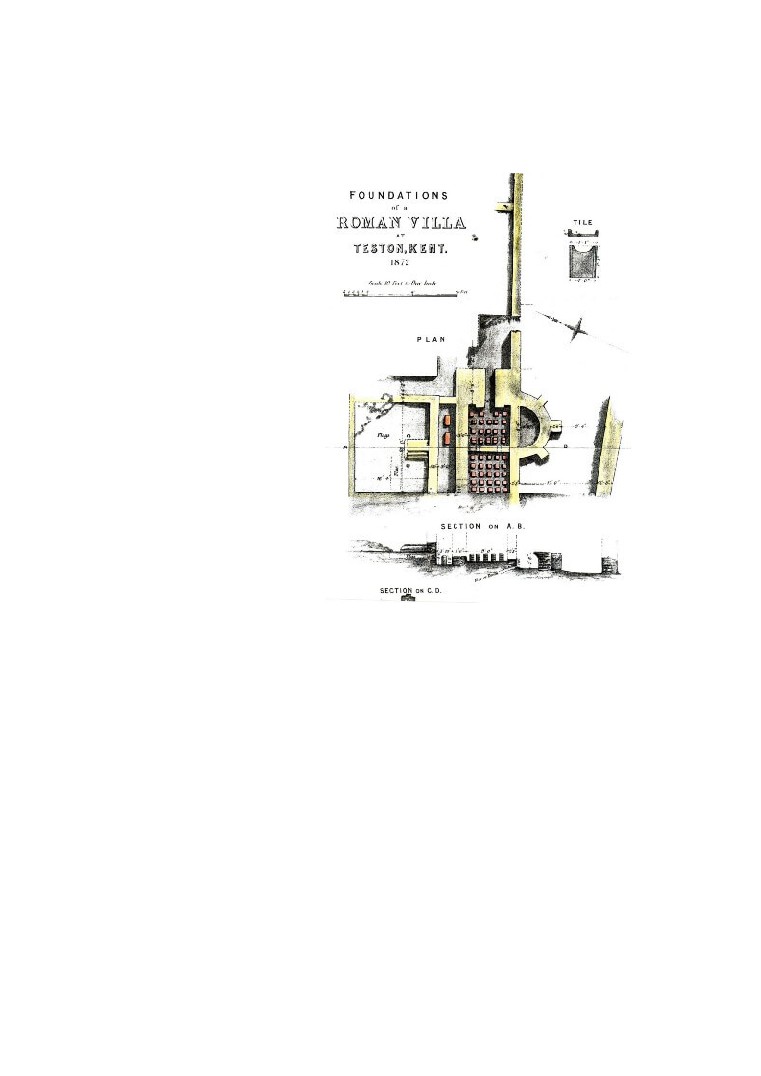

Archaeological test pitting on the site of a recently discovered Roman Villa (or water

mill) at Wye in Kent. On this four day course we shall look at the ways in which

archaeological sites are discovered and excavated and how different types of finds

are studied to reveal the lives of former peoples. Subjects discussed will include

aerial photography, regressive map analysis, HER data, and artefact identification.

This course will be especially useful for those new to archaeology, as well as those

considering studying the subject further. Each day we will participate in an

archaeological investigation on a Roman field system and a building under expert

tuition.

The site is opposite the Tickled Trout pub in Wye and parking is best in the station

car park.

Cost is free if membership is taken out at the time of booking. For non-members the

cost will be £75.

May 28th to June 15th 2018 excavating at 'Villa B' at Oplontis next to Pompeii

in Italy (Fully booked)

We will be spending three weeks in association with the University of Texas

investigating the Roman Emporium (Villa B) at Oplontis next to Pompeii. The site

offers a unique opportunity to dig on iconic World Heritage Site in Italy and is a

wonderful once in a lifetime opportunity. Cost is £175 a week which does not include

board or food but details of where to stay are available (Camping is 12EU a day and

the adjacent hotel 50EU or Airbnb). We will meet at Hotel Mysteries in Pompeii each

details or call 07885700112.

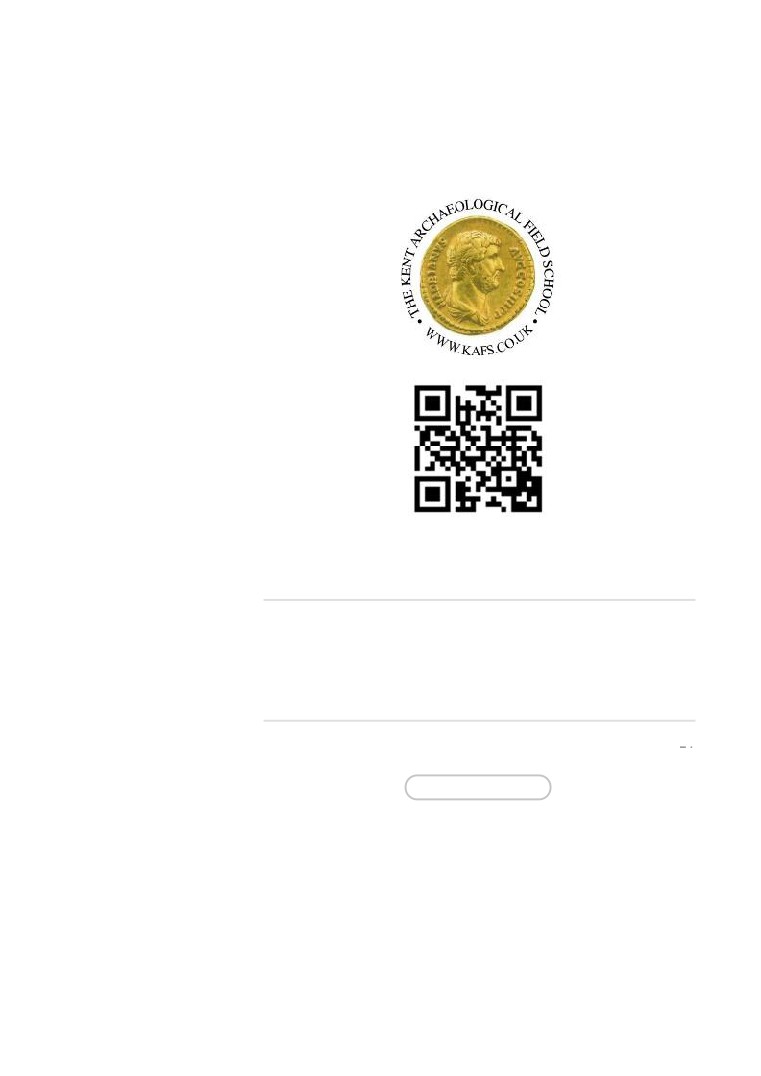

July 30th to August 12th 2018. The Investigation of a substantial Roman Villa

Building at Teston, near Maidstone in Kent

Two weeks investigating a substantial Roman building to find out its form and

function. This is an important Roman building and part of a larger Roman villa

complex which is important to the understanding of the Roman settlement in the

Medway Valley in Kent.

Cost for the day £10 (Members free).

August 6th to August 10th 2018 Training Week for Students on a Roman villa at

Teston near Maidstone in Kent

It is essential that anyone thinking of digging on an archaeological site is trained in

the procedures used in professional archaeology. Dr Paul Wilkinson, author of the

best selling "Archaeology" book and Director SWAT Archaeology will direct the dig

and will spend five days explaining to participants the methods used in modern

archaeology. A typical training day will be theory in the morning (on site) followed by

excavation of the Roman villa.

Topics taught each day are:

Monday 6th August: Why dig?

Tuesday 7th August: Excavation Techniques

Wednesday 8th August: Site Survey

Thursday 9th August: Archaeological Recording

Friday 10th August: Pottery identification

Saturday and Sunday (free) digging with the team

A free PDF copy of "Archaeology" 3rd Edition will be given to participants. Cost for

the course is £100 if membership is taken out at the time of booking. Non-members

£175. The day starts at 10am and finishes at 4.30pm. For directions to the site at

September

10th to

23rd

2018. Investigation of Prehistoric features at

Hollingbourne in Kent

An opportunity to participate in excavating and recording prehistoric features in the

landscape.

The two weeks are to be spent in excavating Bronze and Iron Age features inside a

small prehistoric homestead on the North Downs that was located with aerial

photography and field survey. Cost is £10 a day for non-members, members free.

BACK TO MENU

The Kent Archaeological Field School, School Farm Oast,

Graveney Road, Faversham, Kent ME13 8UP

Director Dr Paul Wilkinson MCIfA

KAFS BOOKING FORM

You can download the KAFS booking form for all of our forthcoming courses directly

from our website, or by clicking here

KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM

You can download the KAFS membership form directly from our website, or by

BACK TO MENU

If you would like to be removed from the KAFS mailing list please do so by clicking here